Corpus Construction

My previous blog, posted on February 15, has since then incrementally grown with a narrower focus for better results.

Throughout the process of constructing my corpus, I have made great strides and a few errors as well. The best term to describe creating a corpus is the term “iterative”. That being said, I realized the magnitude of my task, and I decided to narrow my focus, for now, to compare the Renaissance and Enlightenment texts in my class, HUMN 150. As I precede toward the final weeks of class, I will add the remaining texts and perform the respective analyzes too (See Future Decisions).

The initial steps of creating a corpus are indubitably the hardest. The first step is asking which general question you would like to research. Then, obtaining the documents needed for that research. I decided to create a corpus of all the readings from my Comparative Humanities class, HUMN 150. Throughout the duration of our class, HUMN 100, I intend to compare the 2015 syllabus with the first syllabus from 2000.

Cleaning my corpus was another difficult task. I was able to get the books from Project Gutenberg and one from Professor Faull; however, I acquired the supplementary readings in PDF form through my HUMN 150 instructor, Professor Shields.

I used Adobe Acrobat Pro to convert the PDFs into text files (.txt), and I saved them in my google drive. My google drive is organized by “Renaissance&Enlightenment” texts, “Text Files from Gutenberg,” and “PDFs.” With these folders, I can keep track of which text files I am using. Also, I keep notes on my corpus construction that indicate what I keep and delete in each text file. Then, I cleaned each file by using Spellcheck.net, text fixer.com, and text cleansr.com. Using these websites, I removed line breaks, paragraph breaks, HTML script, and extra white spaces. Additionally, I manually cleaned each file correcting spelling and removing footnotes, some chapter titles, names of authors, and page numbers.

Overall Research Question:

How did the syllabus from 2000 change in terms of genres and authors (gender differences)?

Also, the course was originally titled “Art, Nature, and Knowledge” and is now “Enlightenments,” what is the most accurate title, or what should it be?

General Questions:

Are “God” and “knowledge” prevalent terms throughout the Renaissance and Enlightenment texts? What is dominant?

Is there a gender bias towards female and male authors? Do their writings have gender-preference pronouns?

Do the authors’ lexicon reveal that they are true humanists?

Differential Analysis & Analytical searches with Voyant and Antconc

Voyant was the first platform I performed an analytical search. It is visually-appealing software that allows you to upload your corpus and perform word frequency, collocation, and a multitude of other searches.

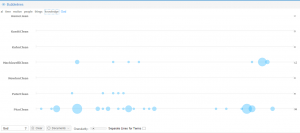

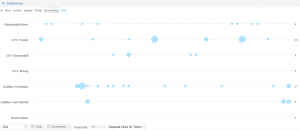

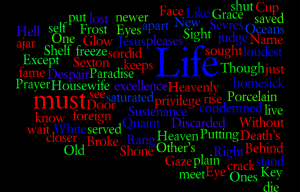

Some of  my recent searches include the terms: “he” “she” “her” and “him”. I was looking for gender bias in my readings. I created a cirrus or word cloud using the maximum of 500 words. I noticed that “he” and “him” was overwhelmingly the most frequent term used throughout by corpus. (see Translation Problems)

my recent searches include the terms: “he” “she” “her” and “him”. I was looking for gender bias in my readings. I created a cirrus or word cloud using the maximum of 500 words. I noticed that “he” and “him” was overwhelmingly the most frequent term used throughout by corpus. (see Translation Problems)

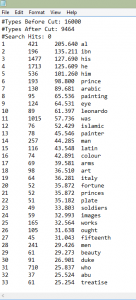

Then, I put the terms “he” and “him” in Antconc, like “he|him” to combine search results. Antconc produced 2249 hits for both “he” and “him”. As for “she” and “her,” there were only 176 hits.

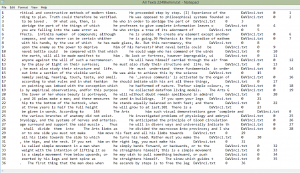

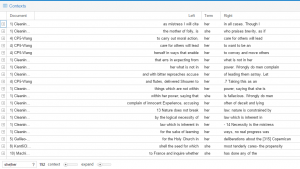

This is a differential search from Voyant looking at some KWIC (keyword in context). I used both “he|him” and “she|her” to research the gender issue in depth. Usually, “he” is used to refer to a general population. The most interesting case is the use of “her” and “she”. The lexicon surrounding these terms is significantly ne

This is a differential search from Voyant looking at some KWIC (keyword in context). I used both “he|him” and “she|her” to research the gender issue in depth. Usually, “he” is used to refer to a general population. The most interesting case is the use of “her” and “she”. The lexicon surrounding these terms is significantly ne gative, such as “folly,”, “mistress,” and “bitter”. Also, “her” and “she” are frequently used to replace “nature” – purity, “law” and “deliberations” – mutable. When I refer to purity, I am speaking of the “sexually pure good girl”. When I use the word “mutable,” I am speaking of the way in which men view women as an object, and how men suppress women into the image they want to see.

gative, such as “folly,”, “mistress,” and “bitter”. Also, “her” and “she” are frequently used to replace “nature” – purity, “law” and “deliberations” – mutable. When I refer to purity, I am speaking of the “sexually pure good girl”. When I use the word “mutable,” I am speaking of the way in which men view women as an object, and how men suppress women into the image they want to see.

On the other hand, the terms surrounding “he” and “him” allude to power. Some of the lexicon items surrounding these terms are “God,” and “Lord.”

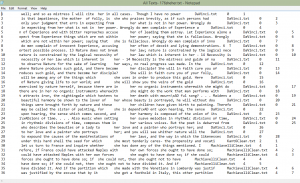

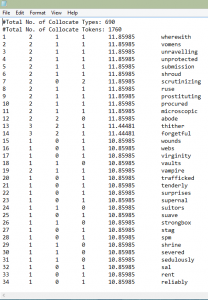

This screenshot is a collocation of “her|she”. This also enables me to see the negative lexicon surrounding the terms “her” and “she” throughout all my texts. There are terms like “submission,” “prostituting,” and “virginity.” This lexicon gives the impression that women are represented in my texts only as pure or “dirtied” and as objects. The greater part of this collocate has a plethora of words with negative connotations and denotations.

This screenshot is a collocation of “her|she”. This also enables me to see the negative lexicon surrounding the terms “her” and “she” throughout all my texts. There are terms like “submission,” “prostituting,” and “virginity.” This lexicon gives the impression that women are represented in my texts only as pure or “dirtied” and as objects. The greater part of this collocate has a plethora of words with negative connotations and denotations.

Comparison of Voyant & Antconc

In this blog, I have differential searches from both Voyant and Antconc. Each platform has its own strengths and weaknesses. Voyant is useful for a brief and illustrative analysis of your corpus. It includes many different tools to view your corpus; however, it is easy for many scholars to challenge your research calling the illustrations “pretty pictures” and stating that they are nothing more. In fact, this is not true. They are visual representations of your corpus statistics. For example, you can put in a unique word like “God” and see the vocabulary density of this word throughout all your texts with a single tool- bubblelines, scatter plot, etc.

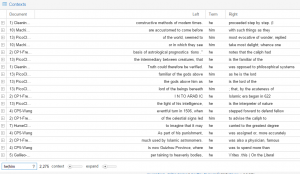

Antconc allows you to view the statistics behind the illustrations of Voyant. It is easy to see the collocations of a word, like “God”. Moreover, Antconc analyzes the frequency of a word (hits) and the terms used around that word (collocates), allowing you to click on a term and see its context in each reading. Antconc also allows you to have a reference corpus. A reference corpus allows you to see the keyness of a certain group of texts with regards to another corpus. For example, I referenced my Enlightenment texts to my Renaissance texts to see the keyness of the Renaissance texts. There were obvious words like “prince” and “painter” instead of words that belong to the Enlightenment like “time” and “motion.”

Antconc allows you to view the statistics behind the illustrations of Voyant. It is easy to see the collocations of a word, like “God”. Moreover, Antconc analyzes the frequency of a word (hits) and the terms used around that word (collocates), allowing you to click on a term and see its context in each reading. Antconc also allows you to have a reference corpus. A reference corpus allows you to see the keyness of a certain group of texts with regards to another corpus. For example, I referenced my Enlightenment texts to my Renaissance texts to see the keyness of the Renaissance texts. There were obvious words like “prince” and “painter” instead of words that belong to the Enlightenment like “time” and “motion.”

Pragmatics

The platforms have given me great insight into the gender markers of my text. The usual stop words like “he” and “she” give me a chance to analyze the gender bias in the 2015 syllabus. Consequently, to answer the overall research questions I will need to upload the corpus of the syllabus from 2000. As of now, I can conclude there is a male bias in my texts and that there are no female authors in the Renaissance and Enlightenment texts.

The terms from the old title of the course, “Art, Nature, and Knowledge”, are prevalent in the text as well.

Translation Problems

The biggest issue with my corpus is that most of the texts are a translation from either German, Italian, Chinese, etc. Thus, I am not always certain that the term “he,” for example in German, was actually in the neuter form. If it was, I have to take into account the translator’s gender bias too. Also words like “Menschheit” in German, which means “mankind” is a feminine noun; however in English, it may be interpreted as a masculine inclusive noun. I will need to take the translations and the translator’s ability into account as I progress with my research.

Future Decisions

As I mentioned above, in the following weeks I will add the remaining texts from my HUMN 150 class and the texts from the syllabus from 2000. Then, I will be able to answer my lingering questions with more evidence. I believe that I am on the right track with my research. I am glad I have narrowed my focus and made the decision to gradually add material. I have learned that digital work takes time. If you wish to have a solid foundation for your corpus, you need to properly collect your material and clean them carefully. As of now, I am excited to learn new platforms and collect new analyses!

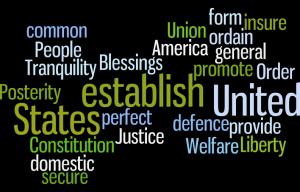

Then I tried to graph “UnitedStates.” I did get a graph, but when I looked at the source texts, the only word highlighted was “United” in the articles. This shows that not all digital tools will work properly with what you want to do.

Then I tried to graph “UnitedStates.” I did get a graph, but when I looked at the source texts, the only word highlighted was “United” in the articles. This shows that not all digital tools will work properly with what you want to do.

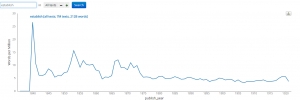

Finally, I tried “The United States” and received an oddly shaped graph. The articles highlighted words like “here” and “mistakes” which have nothing to do with “The United States.”

Finally, I tried “The United States” and received an oddly shaped graph. The articles highlighted words like “here” and “mistakes” which have nothing to do with “The United States.”