For my Final Project I set out to answer the research question I have been attempting to tackle all semester. My question deals with the core ideas and metaphors represented in both C.S. Lewis’s and J.R.R. Tolkien’s magna opera. Both writers were heavily influenced by their beliefs, Tolkien a devout Catholic his entire life, is a often credited as one of the largest factors in Lewis’s conversion from Atheism to Christianity, and later his writings as a Christian Apologist. Both writers had extensive amounts of published and unpublished literature, how could this large part of their lives, seem into their writing. For Lewis, the metaphors are quite clear, Aslan clearly represents a higher being, but what do his actions and his depiction reflect about Lewis’s religious ideas themselves. Tolkien similarly creates deities in his books, and to the same extent as Lewis, writes a Christ-like rebirth scene for one of the higher being protagonists. Surely, these depictions can tell us something about the writers themselves, surely they can reveal ideas upon the writes beliefs. I set out to find answers.

A clear statement of my guiding question are as follows:

1.How do Tolkien and Lewis differ in the ways their writing reflects their spirituality?

2.If so, what can we learn through analysis of their writing?

Furthermore, the individual analyses I did to find these answers

a.Differences in collocates between Narnia Children and Hobbits

b.Similarities in stylometrics regarding the rebirths of Aslan and Gandalf

c.Collocates of heroes during the final scenes of the books

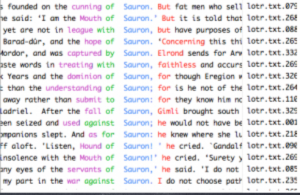

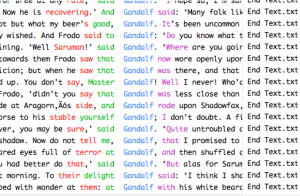

d.Finally, difference in style, and word choice, between fiction and non-fiction works of both authors

The first question, was actually recommended to me by professor Faull. It brings up an interesting perspective because the Hobbits and the children both play pseudo-hero roles, often being outshone by their deified counterparts, Gandalf and Aslan respectively, yet they are also both supposed to personify the most ideal, noble, heroic, and even holy characteristics.

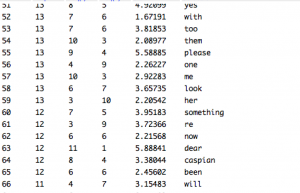

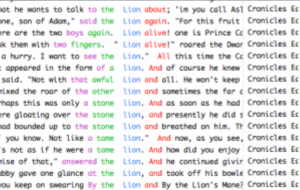

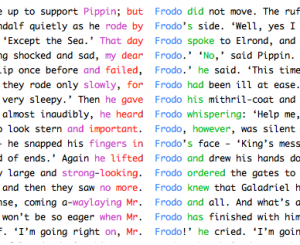

On the left, you will find collocates of Lucy, the only child present in all the books of Narnia, and on the right, you will find collocates of Frodo, the most protagonist Hobbit in Lord of the Rings. Upon a glance, and only from the small screen shot I have provided, a viewer can tell that words like “dear” “please” seem far more pleasant than “cried” (it is worth mentioning that some of the words not pictured here for Lucy were “nice” and “kind”, while some of the other more popular words for Frodo were “poor” and “saddened”). This reminded me of data I presented earlier in the year, that yielded similar results, but with completely different parameters.

So here, as I noted in my midterm review, Lewis uses words to belittle his christlike character, while Tolkien to the same effect, empowers his satan-like character. Both create a narrative where the weaker protagonist must overcome the stronger antagonist; clearly biblical references especially considering both protagonists sacrifice themselves and are brought back to life. Where the authors do differ is in the previously mentioned depiction of the children and the Hobbits. Both play similar roles in the stories, eventually becoming the main protagonists and heroes, but through the analysis one can tell that along their journey Tolkien seems to humanize the Hobbits by exemplifying their flaws, while Lewis reg-ifies Lucy.

Does this mean that Lewis recognizes the inherent good in people mentioned in the bible and that Tolkien instead recognizes every humans tendency to sin also mentioned in the bible? Both depict their heavenly figures in similar ways, but the ways in which they depict their humans in quite interesting.

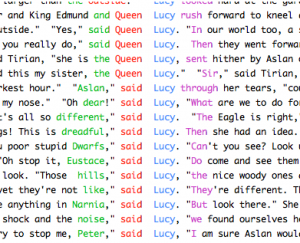

Another interesting plot development I discovered about the works, was their depictions of their characters as the plots ended. Again using Frodo and Lucy, Professor Faull suggested I checked the collocates towards the end of each respective work.

While Lewis’s characters grow in maturity, wisdom, and fortitude, Tolkien’s Frodo seems to be drained of these qualities throughout the end of the novel. And given the scene in Mount Doom anyone could note the degradation of Frodo, I think it is important to point out that this decline was not as sharp as it might have seemed. In fact, in the second half of the 3rd book, almost all of Frodo’s collocates are negative. Lucy on the other hand, is continuously regarded even more highly.

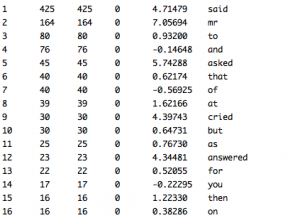

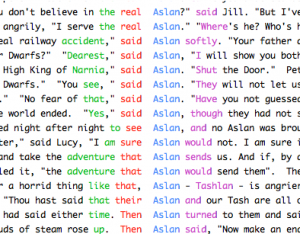

I went further and also compared the collocates of both Aslan and Gandalf.

Aslan, towards the end of Narnia, seems to lose importance, and the emphasis is shifted to Lucy and company. Gandalf, on the other hand, maintains all of his clout, with Frodo staring with “eyes full of terror at Gandalf”.

If you consider all of this information together it makes sense. Through my analysis, we learned that Tolkien places far more emphasis on his deities, while often showing the flaws of his human characters. Lewis conversely, eventually has his human characters surpass his deity. All of this can be argued and drawn from the data above.

We also know that Lewis was an former atheist, who converted to Catholicism, which would explain how his writings could reflect the declining powers of the works god. Tolkien, a lifelong Catholic, even at the ends of his work, maintains the power and place of his deities.

Based on these conclusions, I would state that, while it is widely accepted that the Chronicles of Narnia are a biblical story, The Lord of the Rings is more religious.

My Corpus: https://drive.google.com/drive/u/1/folders/0B4ATX3PFP8CYOV9nN01kdV9UVUE

Bibliography

Jiayu Huang– Lord of the Rings parsed and cleaned text

All other texts were downloaded from:https://b2dbuntu.wordpress.com